(Start sub-menu)

Sample Chapter

(End sub-menu)

On This Page

(Start local sub-menu)

(End local sub-menu)

Last updated:

24. July 2001

(Start sub-menu)

Sample Chapter

(End sub-menu)

On This Page

(Start local sub-menu)

(End local sub-menu)

As with skinning a cat, there is more than one way to start a Win32 application. There are GUI ways and there are console ways; some of them have to do with shell integration, a concept that is also touched in Chapter 20, Setup.

Listing 24: Exploring the Command Line

int WinMain( HINSTANCE, HINSTANCE, LPSTR pszCmdLine, int ) { MessageBox( 0, pszCmdLine, "Arguments", MB_OK ); }

This simple program proved helpful for exploring the results of various actions.

The starting of an application has two sides—the outside and the inside. This chapter is mostly concerned with the inside, in particular, all the possible values of the pszCmdLine parameter to WinMain. This is not as trivial as it sounds.

In the following, I assume that the GUI shell is the Windows Explorer. While other shells are certainly possible, they’d better deliver similar functionality if they want to survive in the market place.

TextEdit can be started directly in several ways. After selecting the TextEdit icon, you can double-click, right-click and select Open from the context menu, or hit the Enter key. The result is in any case that the shell calls CreateProcess, and eventually TextEdit’s WinMain is invoked.

The pszCmdLine parameter is now empty. In a situation like this, Notepad lets you edit an “untitled” file, one that exists in memory only. TextEdit, on the other hand, has a conceptual model that supposedly works directly on files—there is no concept of a separate memory image. Although this is an illusion, it means that untitled files are out—we must create a suitably named file in a suitable location. This is handled by the createNewFile function in createNewFile.cpp.

A user’s default data directory can be retrieved using the SHGetSpecialFolderLocation function with the CSIDL_PERSONAL parameter. On my machine, this defaults to C:\WinNT\Profiles\myUserName\Personal. Being inside the system directory, this doesn’t strike me as a particularly good place to store user data, so the TextEdit installation program allows users to select a different default directory. This location is maintained through the Options dialog.

If you wish to edit the file sample.txt, you can drag an icon representing the file onto the TextEdit icon. This time, pszCmdLine points to the full path of sample.txt, and TextEdit opens the file. Most sample programs handle this straightforward case correctly.

You can also drag multiple files onto the TextEdit icon. This is where it starts getting moderately messy; the shell strings all the file names together with a space between them:

c:\sample1.txt c:\sample2.txt

Figure 6: Notepad in Action.

Parsing two consecutive file names as one doesn’t always work.

Now what? Since TextEdit is an SDI application, we can only open one file per instance. Unless you want to get bizarre, the only answer is to start more TextEdit instances. The primary instance of TextEdit (the one invoked by the shell) parses the parameter list and takes the first file name for its own. Then it starts a new instance of itself, passing the remaining file name parameters to the new instance. This starts a cascade of recursive invocations that bottoms out when the final instance gets but one file name, poor thing.

Notepad treats the whole command line as a single file name, which may lead to the problem shown in Figure 6.

The problem here appears to be the second colon, which makes the file name syntactically invalid. Try it from the command line, omitting the offending syntax:

notepad sample1.txt sample2.txt

Figure 7: Notepad in Action again.

Two consecutive file names constitute a valid file name, but the file does not exist.

This message box may not look too bright, but Notepad’s strategy actually turns out fine if you forget to quote a file name containing spaces. TextEdit also tries this approach before considering each argument as a separate file name.

These are the direct ways you can start the app from a GUI shell; they work with all applications and all data files. If the shell knows that TextEdit is associated with a specific file type (such as .txt), other possibilities open up.

You can open a text file by double-clicking its icon. The shell looks up the application association with .txt files (and if that application is still Notepad, you and I are no longer on speaking terms) and starts the program, passing the file name in pszCmdLine.

You can do this with multiple files, too. Select a bunch of files, and press Enter. From the user’s point of view, this is much the same as dragging one or more files onto the TextEdit icon. What happens behind the scenes is quite different: instead of passing all the file names to a single TextEdit instance, the shell starts one instance of TextEdit for each file opened.

There’s another difference: If you drag text files onto the TextEdit icon, the file names sent to TextEdit are converted to the short 8.3 form, if necessary. If it didn’t, any file names with spaces would screw things up. The up side of this is that we don’t have to worry about spaces in the file names when parsing the command string. The down side is that we need to convert all file names to their long forms before displaying them to the user.

If you Open a bunch of text files, the file names sent to TextEdit are in their long form. Since long file names may contain spaces, each file name must be enclosed in double quotes. If not, TextEdit will assume that there are multiple file names on the command line. The shell does not put on the quotes for you; you have to specify this in the registry entries, e.g.:

[HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\txtfile\shell\open\command] @="\"C:\\Program Files\\TextEdit\\TextEdit.exe\" \"%1\""

Notepad’s registry entries neither have nor need the quotes, by the way, as Notepad interprets the command line as a single file name anyhow.

I shall describe the registry in more detail in later chapters.

The shell also supports printing. If the right entries are set in the registry, the shell displays a Print command on the context menu whenever you right-click sample.txt. The Print command starts TextEdit with the following pszCmdLine:

/p "c:\sample.txt"

It is our responsibility to recognize the /p switch and to act appropriately.

Alternatively, you can drag sample.txt to a printer icon. This results in a printto command, which is a little more complicated—it is taken as an order to use a specific printer, rather than the default printer. The printto command has the following general form:

/pt <file_name> <printer_name> <driver_name> <port_name>

Here is a sample pszCmdLine:

/pt "c:\sample.txt" "HP DeskJet 600" "RASD.DLL" "LPT1:" )

If you use Shell integration to Print multiple files, the shell starts a new TextEdit instance for each, so we need not worry about multiple /p or /pt switches.

Another shell integration concept is the SendTo folder. You don’t need to mess with the registry to use it; just create a shortcut to TextEdit.exe in the SendTo folder. This adds a “TextEdit” entry to the “Send To” submenu of the Explorer’s context menu. The result of using the Send To command is the same as when you drag tiles onto the TextEdit icon, i.e., a single application instance receives a string of one or more 8.3 file names separated by white space.

Windows NT maintains one SendTo folder per user.

To sum up, the GUI shell can give us the following command lines:

Let us leave the GUI shell for a while, and look instead at command line interpreters, or shells. The standard command shell for Windows 9x is command.com, while the one for Windows NT is cmd.exe. For our purposes, their behaviors are similar enough to ignore their differences.

You can start TextEdit by typing textedit at the command prompt. If you start a console program this way, the command shell waits patiently until the program has finished executing. A console program is marked /SUBSYSTEM:CONSOLE at link time. TextEdit, however, is marked /SUBSYSTEM:WINDOWS at link time, so the command shell returns to the prompt immediately after calling CreateProcess.

As with the GUI shell, you can pass one or more file names as parameters to TextEdit. Any file names that contain spaces should be enclosed in quotes, but aside from that, you’re free to mix long and short, quoted and unquoted forms. The command line is total chaos compared with the GUI shell.

(This illustrates one of the great advantages of the GUI paradigm, namely the use of constraints. Rather than typing a command, you must select it from a menu; rather than typing a file name, you are forced to select it from a list. Typos are no longer possible, and one source of errors is eliminated. The GUI constraint paradigm also illustrates the best possible form of “error handling:” redesign the application so that the source of the error goes away.)

What happens if you type something like “TextEdit *.txt”? That depends on the command processor you are using. UNIX command shells expand wildcards automatically, resulting in a command line of, say, “textedit sample1.txt sample2.txt.” Unfortunately, neither command.com nor cmd.exe do wildcard expansion, so TextEdit must deal with this on its own.

On the face of it, this would seem to require special treatment of arguments with wildcards, but this isn’t so. In the first place, if you treat sample.txt as a wildcard pattern and do a search using FindFileFirst and FindFileNext, you will find exactly one matching file, namely sample.txt. We can, in other words, treat all arguments as wildcard patterns without getting into trouble.

Even better, we can sidestep the whole issue by linking with setargv.obj, which gives us wildcard expansion for free. (Most compilers come with a similar relocatable object file, though it might have another name, such as wildargs.obj.)

If no files match, the program is passed the exact parameter string as typed, i.e., “*.txt”.

If you try passing *.txt to Notepad, it complains that it “cannot open the “*.txt” file.” This happens no matter how many files match the pattern. Notepad also tells you “to make sure that a disk is in the drive specified,” and the user is left wondering whether the program has suffered brain damage. Oxygen deprivation, perhaps. The least we can do is to recognize the alleged file name as a wildcard pattern, and report that no matching files were found.

What about long versus short file names? That doesn’t require any special treatment either. The function GetLongPathName converts short names to long names, but if it is fed a long name, it will simply return that name. In other words: all file names—long and short—may safely be passed through GetLongPathName.

The one unfortunate thing about GetLongPathName is that it’s only available on Windows 98 and Windows 2000. Consequently, TextEdit has its own function, called getLongPathName, defined in getLongPathName.cpp.

A different, and possibly better, approach to the implementation of getLongPathName would have been to apply FindFirstFile to each path element in turn.

Wild cards require no special treatment, nor do long and short file names. This illustrates a design principle:

“If possible, avoid special cases.”

Special cases require more code; in particular, they require branching. This makes testing that much harder and gives bugs additional opportunities to creep in. Bugs abound anyhow; why invite more?

Nevertheless, one particular kind of file does require special treatment: the shortcut. Win32 “shortcuts” are not real links, merely files with a .lnk extension. The file system does not resolve shortcuts; the Explorer does. If you double-click a shortcut, the Explorer resolves it before handing you the file, so no special handling is necessary. Not so the command-line shell; you’re fed the .lnk file, and that’s that.

This is all handled by the function resolveName (see resolveName.cpp); its job is to figure out if the file is a link, and if so, to figure out which file the link references. All files pass through resolveName; the special handling is hidden on the inside. The inside, by the way, uses the IShellLink COM interface to resolve the link.

Resolving links is an issue with the Open common dialog as well. This dialog is discussed in Chapter 14, File Management.

Consider the following command line:

C> textedit sample1.txt sample2.txt /p sample3.txt sample4.txt

Should we print all the files, or only the one immediately following the /p switch, or all the files following the /p switch? Or should we disallow the whole command line on grounds of silliness?

Handling all possible variations in a reasonable way requires unreasonable contortions. TextEdit does allow the invocation, by printing all the files. Any other interpretation would be needlessly complex, both for the user and the programmer.

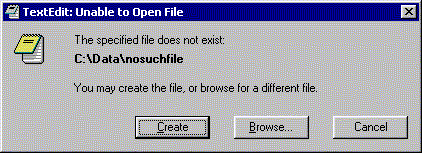

Figure 8: TextEdit can’t find a file.

You may create a new file or browse for an existing file.

What if a file doesn’t exist? There are several ways to handle this, and Notepad is quite sensible about it—Notepad asks the user if it should create a new file by the given name. TextEdit extends this a bit: It explains that the file does not exist, and the user is presented with the following choices:

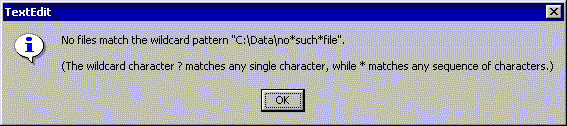

If the file name contains wildcard characters, the procedure is slightly different, as you can’t create a file with wildcard characters in the file name. TextEdit explains that no matching files where found, and goes on to explain what a wildcard character actually is.

Figure 9: No files match a wildcard pattern.

Since some users will be unfamiliar with wildcards, the message box explains the concept. The explanation is not so intrusive as to bother power users.

From there, the choices are as above, except that creating the file as named is obviously out of the question.

Even if a file does exist, there are potential problems. The user may have limited access rights, or perhaps the file has been locked by a different application. Chapter 12 (File I/O) deals with this.

A file can be read-only in many ways, some more permanent than others:

In other words, the file might be read-only, or the file’s location might be read-only. Or not even read…

What happens if you double-click sample.txt while you are already editing the file with TextEdit? We have two possibilities—either we open the file in a second instance of TextEdit, or we bring the first instance to the top. Notepad takes the first route, which is a reasonable one for a traditional program. This paradigm has caused endless confusion and heartache among users that never realized they had five letters to grandma open at once. Besides, it fits badly (to put it mildly) with the unified file model, so TextEdit takes the second route. Before opening sample.txt, it checks whether the file is already open in a previous instance of TextEdit. If so, that instance is brought to the top, and the new instance quietly terminates. This is handled by activateOldInstance (see activateOldInstance.cpp).

Conflicts and problems are still possible, of course—the file might be open in a different program, or the user may rename or delete the file while we’re editing. The file may reside on a removable volume that is removed, or on a network server that just crashed.

Multiple instances of the same file on a command line don’t cause problems; this is handled automatically.

Consider the following command line:

C> dir | textedit

Wouldn’t it be nice if the output from the dir command were to appear in TextEdit? This was not a viable proposition under Win16, but it’s dead easy under Win32. The following call works even for GUI programs:

HANDLE hIn = GetStdHandle( STD_INPUT_HANDLE );

To stay in character, TextEdit must of course create a file in which to keep the standard input. This is handled analogously to creating a new file, by the same function, createNewFile (createNewFile.cpp).

Mixing file name parameters with piping works just fine; the following will edit both sample.txt and the output from the dir command, in two separate instances of TextEdit:

C> dir | textedit sample.txt

If you wish to print a file from the command line, this is one convoluted way of doing it:

C> type sample.txt | textedit /p

Command-line pipes are only for experts such as thee and me—a beginner won’t even realize the capability is there. Power users will love it, though, and don’t forget that beginners and intermediates rely on experts for advice on what software to buy. Cater to your power users!

So far, we’ve talked of dragging one or more text file icons onto the TextEdit icon. You can also drag a text file icon onto a running instance of TextEdit. TextEdit identifies itself as capable of handling the WM_DROPFILES message by calling DragAcceptFiles during main window creation, so the Explorer will happily send us a WM_DROPFILES message. In response, TextEdit will open the dropped file in place of the current file.

What should we do if somebody drops multiple files on us? That is actually a somewhat thorny problem. For an MDI application, it is perfectly natural to open multiple files, but for an SDI application, this would be a distinctly unnatural act.

Notepad ignores all the files but one, which is certainly a reasonable design decision. Another possibility would be to string all the files together into a composite. This is perhaps the most “natural” action possible for an SDI application, but really too bizarre for serious consideration.

What TextEdit actually does is open one of the files in the existing window, and start new instances for all the others. This is a conceptually imperfect solution, but it’s the best I can think of.

Handling the WM_DROPFILES message involves two functions: DragQueryFile and DragFinish. The handler can be found in mainwnd.cpp, and it looks like this:

LOCAL void onDropFiles( HWND hwnd, HDROP hdrop ) {

const UINT DRAGQUERY_NUMFILES = (UINT) -1;

const int nFiles = DragQueryFile(

hdrop, DRAGQUERY_NUMFILES, 0, 0 );

for ( int iFile = nFiles—1; 0 <= iFile; --iFile ) {

PATHNAME szDragFile = { 0 };

verify( 0 < DragQueryFile(

hdrop, iFile, szDragFile, dim( szDragFile ) ) );

if ( 0 == iFile ) {

getEditor( hwnd )->openFile( szDragFile );

} else {

startInstance( szDragFile, SW_SHOW );

}

}

DragFinish( hdrop );

}

If the DragQueryFile function is invoked with the second parameter equal to -1, the function just returns the number of files dropped; otherwise, the second parameter is an index.

TextEdit understands several other switches. Some, such as /min and /max, are conveniences, while others, such as /setup, allows the single executable to function in several completely different ways. The complete list of command-line switches is summarized in the following table:

| Option | Explanation |

|---|---|

| /boot | Checks the registry for files marked “running,” and starts a TextEdit instance for each. |

| /edit | Forces use of the standard edit widget rather than the rich edit widget. This switch is only available in debug builds. |

| /last | Opens previous file (MRU 1). |

| /min | Start TextEdit minimized. |

| /max | Start TextEdit maximized. |

| /p /print | Print, showing the print dialog. |

| /pt /printto | Print to a specific printer, don’t show the print dialog. |

| /setup | Start the TextEdit installation and maintenance subsystem. A TextEdit installation disk should include either Setup.exe.lnk (a shortcut to “TextEdit.exe /setup”) or a TextEdit executable renamed to setup.exe or install.exe. |

Should we allow the hyphen to signal command-line switches? The hyphen, or minus sign, is the standard option signal on Unix, and many DOS and Windows programs accept it in addition to the slash. There is only one hitch—it is perfectly legitimate to start a file name with a hyphen.

No conflict arises when TextEdit is started from the GUI shell. Any hyphens are certain to be somewhere inside the path name, and so won’t be recognized as the start of a switch. From the command line, however, it is necessary to say something like textedit .\-myFile.txt rather than textedit -myFile.txt. Otherwise, TextEdit gets confused by the myFile switch, which it has never heard of.

To confuse things further, the slash is a perfectly good separator of path elements. It’s only the internal commands in COMMAND.COM and CMD.EXE that think otherwise; the file system is happy with slashes going either way.

In TextEdit, both the slash and the hyphen signal a switch, but all unrecognized switches are assumed to be file names. In init.cpp, you will find some vestigial code that warns against unrecognized options. I removed that code after writing the above couple of paragraphs, and TextEdit will now happily accept both /myDirectory/-myFile and -myFile as arguments.

This confusion has two drawbacks. A misspelled switch is treated as a file name, and files with option names need some path decoration on the command line (e.g., the file -max must be specified as .\-max or ./-max). Even more confusing, specifying textedit * in a directory that only contains the file ?max, will result in the editing of a new file in a maximized window, hardly what was intended. (Specifying textedit .⁄* works, though.)

We live in an imperfect world, and can only do the best we can. These drawbacks are not serious enough to lose sleep over.

I’ve talked a lot about pszCmdLine in this chapter, but we don’t actually use it. We could, but we would then have to parse it, something the C Runtime Library (CRT) is perfectly capable of doing for us.

The main function of a console application gets its parameters in predigested form, with argc giving the number of arguments, and argv giving the arguments themselves. This parameter parsing does more than just find all the white space; it also handles quoted arguments correctly. It turns out that argc and argv are accessible from /SUBSYSTEM:WINDOWS programs, too, through the global CRT variables __argc and __argv.

The ArgumentList class is in charge of command lines. In addition to wrapping access to __argc and __argv, it handles the command line switches (options).

(Start bottom menu)

Top •

Home

• Articles

• Book

• Resources

Windows Developer Magazine

• R&D Books

• CMP Books

Amazon.com

• Amazon.co.uk

• Contact Petter Hesselberg

(End bottom menu)